So you’ve got to write a research paper or some other type of composition that requires you to include information from outside sources. And your instructor or boss says that your citations need to be in MLA format. No problem!

Read on to find out what you need to know about MLA citations.

What Is MLA Format?

MLA stands for Modern Language Association.

While the MLA does more than produce a formatting handbook or style guide, that’s what most of us probably know them for.

The MLA handbook is one of several style guides that standardizes the way scholars format their work, and cite and document sources in their work. The standardization makes it easy for readers to recognize the sources used and provides the information they need to find that source themselves, should they want to explore it further.

The MLA handbook is one of several style guides that standardizes the way scholars format their work, and cite and document sources in their work. The standardization makes it easy for readers to recognize the sources used and provides the information they need to find that source themselves, should they want to explore it further.

What Is an MLA Citation?

A citation is an acknowledgment of your source—an attribution—in which you ascribe a work, quote, etc. to an author. MLA citations are citations that follow the formatting of MLA guidelines. Other style guides (e.g. APA, Chicago) have different formats.

In-Text Citation

When you put MLA citations within the body of your paper, they are called in-text citations. Your MLA in-text citations may be accomplished through attributive language, a parenthetical citation, or a combination of both.

Attributive Language

When you use attributive language, you include recognition of your source in your text. For example, if I am referring to information from Carl Zimmer’s New York Times article, “A New Company With a Wild Mission: Bring Back the Woolly Mammoth”—which reports on a team of scientists at Colossal Biosciences who want to use DNA to recreate and resurrect the woolly mammoth—I could write:

In his article, Zimmer reports that “The scientists will try to make an elephant embryo with its genome modified to resemble an ancient mammoth.”

If the reference marked the first time I was using Zimmer’s article, I would include the title of the article after the phrase “In his article,” and surround the title with commas, like this:

In his article, “A New Company With a Wild Mission: Bring Back the Woolly Mammoth,” Zimmer reports that “The scientists…”

Parenthetical Citation

The specific information required in a parenthetical citation can vary depending on the type of source that’s being referenced, so it’s important to check those details with the style guide.

Often, the parenthetical citation includes the author’s name and the page number from which you borrowed your information. If I were including a quote from the book I’m reading right now, My Lovely Wife, my citation would look like this:

The narrator reveals his growing distress, stating “Ever since they found Lindsay, I have not slept well. I wake up at night, my heart pounding, and it is always about some irrational thing” (Downing p.30).

But what about a parenthetical for Zimmer’s article? I found it online where there are no page or paragraph numbers.

- If the paragraphs were numbered, I would use (Zimmer par.4).

- Since the paragraphs are not numbered, I would simply use the author’s name (Zimmer).

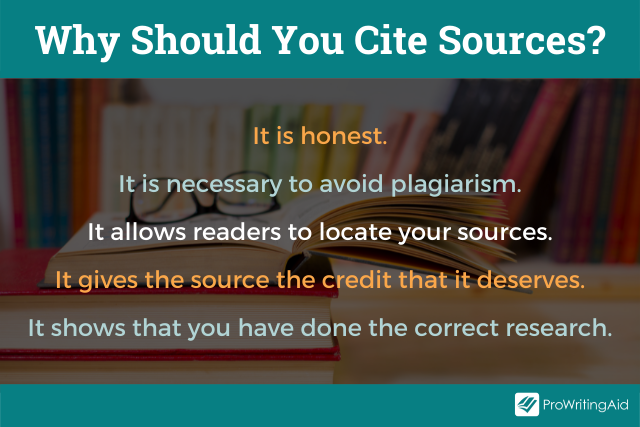

Why Is Citing Sources Important?

It might be easier to write a paper and not cite—acknowledge—the sources you borrowed from, but it wouldn’t be honest; it wouldn’t leave your reader with a trail of breadcrumbs they could follow directly to the source, and it wouldn’t show the true depth and substance of your work.

Using Citations for Honesty

Have you ever told someone a joke and then later they share that joke with a larger group, garnering great laughs but never crediting you as the source of the joke? Kind of annoying, right? Maybe a little silly and petty as well, but annoying. We like to get credit for our work—even if it’s a joke!

When you borrow information from another source, that author deserves that credit. However, the credit you give is not so much to soothe an ego but to uphold ethical standards of academic honesty and integrity, and in some cases, legal standards. If you borrow information from another source and use it in your own work without citing that source—without crediting the author—you have plagiarized.

What Is Plagiarism?

According to Merriam-Webster, plagiarism is:

To steal and pass off (the ideas or words of another) as one’s own: use (another’s production) without crediting the source.

To commit literary theft: present as new and original an idea or product derived from an existing source.

There are some serious words and phrases in that definition: “steal,” “commit literary theft.”

As writers and scholars, our honesty contributes (or takes away if you’re dishonest) to our credibility. In being honest in citing our sources, we give them the credit they deserve, but also add to the ethos—the credibility and trustworthiness—of our own work.

Did you notice how I credited my source for my definition? I used the attributive phrase, “According to Merriam-Webster...”

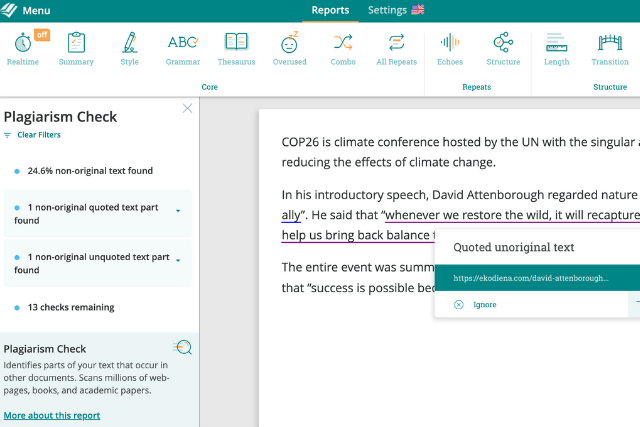

For extra help in avoiding plagiarism, sign up for ProWritingAid’s Plagiarism Checks. Unlike other plagiarism checkers, ProWritingAid will not store or share your work. Ever.

Using Citations to Leave a “Trail of Breadcrumbs”

Do you know the story of Hansel and Gretel? It was written by Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm, also known as The Brothers Grimm.

Here’s a quick summary:

Hansel and Gretel live with their father, a kind woodcutter, and their unkind, unloving stepmother. The family was extremely poor, and the stepmother determined the children would have to go so that the parents could have enough to eat. She told the woodcutter her plan: they would take the children into the woods for a picnic of sorts, and then abandon them and let nature take its course with them. However, Hansel heard her plan and created one of his own. He collected little white stones and dropped them as the family walked into the forest so that he and Gretel could find their way home. It worked! But the stepmother tried the plan a second time, and this time Hansel brought breadcrumbs to leave a trail. The birds ate the breadcrumbs, so there was no going back!

The story continues—there’s a candy house, a witch, and an oven, a duck, and riches, but the part of the story relevant to MLA citations is the trail of stones and the trail of breadcrumbs.

The trail of breadcrumbs from the story has become part of our language. We use the phrase to indicate that bits of information are connected and ultimately can be followed back to a source.

When you cite your sources in your work, you leave your reader a trail of breadcrumbs leading back to that source.

For example, in my citation above, you can see the title of the article I quoted in the parenthetical citation. I had to use the name of the article since there is no stated author. That parenthetical citation is the first breadcrumb in the trail.

When you look at my list of works cited, at the end of the post, you’ll see the next part of the trail that will ultimately lead you to the source.

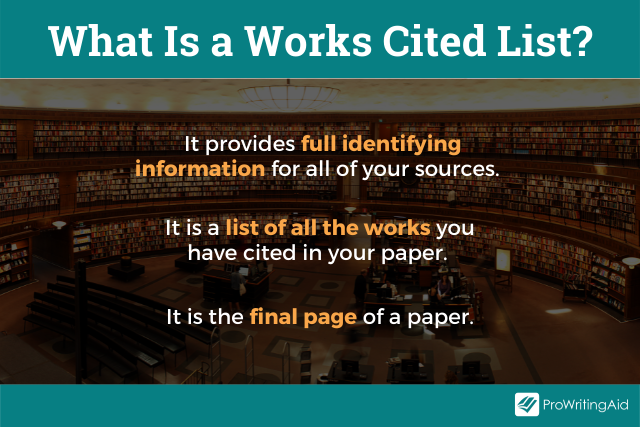

What Is a Works Cited List?

Your works cited page is the last page of your paper. It is the end of your trail of breadcrumbs and provides full identifying information for all of your sources. On it, you list all of the works—sources—you have cited in your paper.

That means that any source you acknowledge in your paper must appear on your works cited list. If you do not cite a work in your paper, it should not appear on your works cited list.

This list presents your sources in alphabetical order by author, unless there is no author. In that case, the title would be the first part of the entry. Your reader can locate the name of the author or title acknowledged in the paper on the list and find complete identifying information on the source so they can find that source easily on their own.

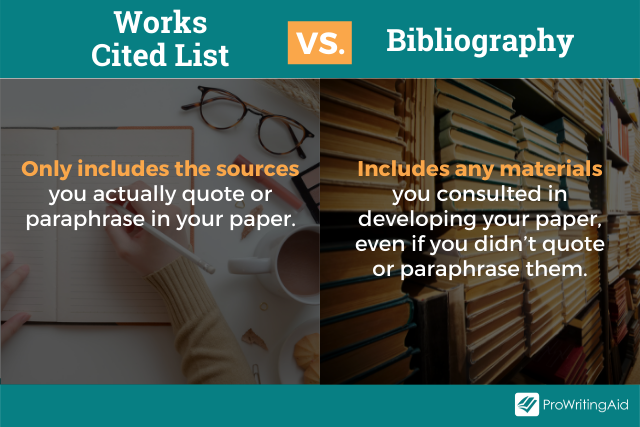

How Is a Works Cited List Different from a Bibliography?

A works cited list includes only the sources you actually quote or paraphrase in your paper. If you quote or paraphrase from five sources in your paper, then those five sources are the only ones that should appear on the works cited list.

A bibliography includes any materials you consulted in developing your paper, even if you didn’t quote or paraphrase from them directly.

Using Citations Proves Your Work Is Credible

When you use other sources to support your points or arguments, you provide support for your point. You’re verifying that what you’re saying isn’t simply an idea you concocted, but a concept, idea, or argument that is supported by other information. The actual content of the support will depend on the type of paper you’re writing.

If the thesis of your paper is Consuming diet soda can cause a variety of health complications, your borrowed information might include information from studies that show this connection, like this:

Though sugar-sweetened drinks carry their own health implications, artificially sweetened drinks, such as diet soda have even more negative effects: “a 2019 study found women who had more than two servings a day—defined as a standard glass, bottle or can—had a 63 percent increased risk of premature death” (Lamotte).

If the thesis of your paper is Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho marked a seminal moment in movie-making history and in culture, your borrowed information would likely include comments from expert filmmakers on Hitchcock’s methods, from reports or articles about the cultural impact of the film on society-at-large. For example:

In the famous shower scene, Hitchcock uses quick edits; he makes over 90 cuts within 45 seconds to create the illusion of graphic violence (Jones qtd. in Hudson).

In both of these examples, the borrowed information does not represent “common knowledge.” It’s specific and from authoritative sources, and your citations allow your readers to see that your ideas have a foundation with experts.

Did you notice the added “qtd. in” phrase to the second example? That phrase acknowledges that the speaker of that quote is not the same as the author of the article. The speaker was “quoted in” the article.

By citing that study or quoting an expert involved in the study, you show that your conclusion is based on valid evidence; you didn’t just make it up.

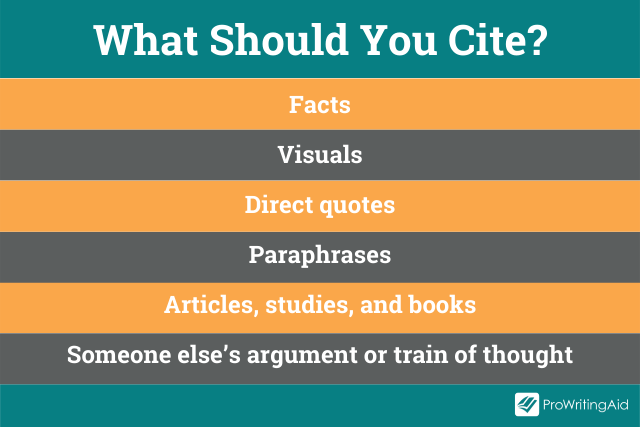

What Should Be Cited?

You need to cite your sources, whether through attributive language or a parenthetical citation, and then include them as entries in your works cited list for all of the following:

- Direct quotes: whether they include entire sentences or phrases

- Paraphrases: information you have rephrased or “translated” into your own words

- Words or terms that are particular to the author’s research or ideas

- Someone’s argument or train of thought

- Facts: for example, historical or scientific facts, or statistical information

- Visuals: such as graphs or charts that you borrow from a source

- Articles, studies, books, etc. that you refer to within your paper

There are also categories of information you don’t need to cite.

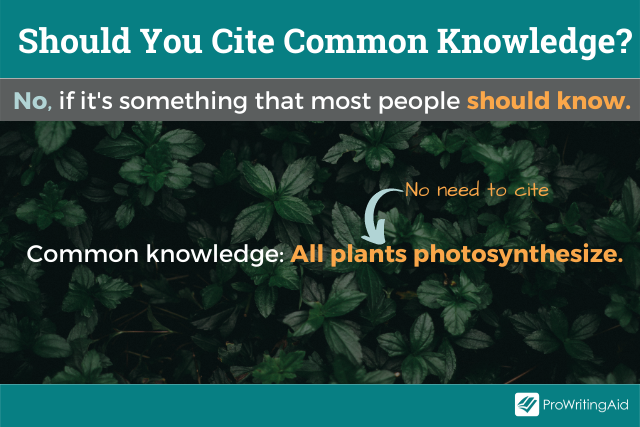

Common Knowledge

Some information falls into the category of “common knowledge.” Merriam Webster defines common knowledge as “something that many or most people know.” Common knowledge does not require a citation. A person wouldn’t have to look up the information to know it is true.

For example:

- Earth revolves around the sun

- There are 52 weeks in a year

- London is the capital of England

- Christmas is celebrated every year on the 25th of December

Common knowledge includes well-known historical dates and people (George Washington was the first American president); basic math (2+2=4); capital cities; long-established facts (the earth is round); and common-sense/obvious observations (grass is green).

Sometimes it’s tricky to determine what qualifies as common knowledge. You can ask yourself a few questions to help make your decision:

- Who is my audience? What can I assume they know?

- Can this information be found in many different places?

- Is this information undisputed and easily verified?

If you’re still uncertain after asking those questions, your best bet is just to cite the information—better safe than sorry. And that saying leads us to another category of information you don’t have to cite...

Common Proverbs

Sometimes, bad things happen, but then good things ultimately come as a result.

For example, you lose your job, but then get another one that you like even more. So, you might say, “every cloud has a silver lining.”

Common sayings like this (honesty is the best policy; every rose has its thorn; blood is thicker than water, and many others) don’t require a citation.

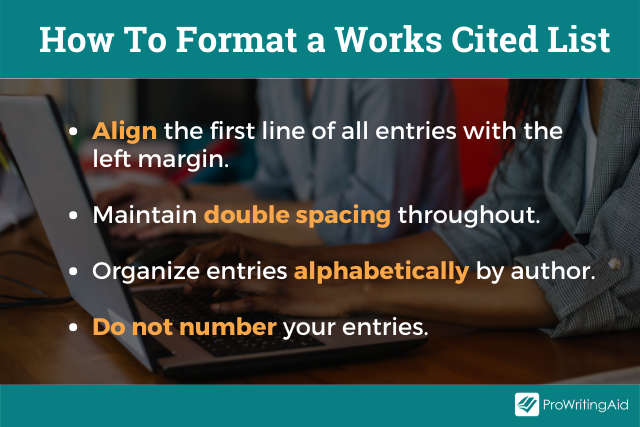

How Do You Format a Works Cited List?

These are the general formatting guidelines for a works cited page:

- Center the title Works Cited at the top of your page.

- Align the first line of all entries with the left margin.

- If an entry has more than one line, indent the second, third, etc. lines of the entry, and go back out to the left margin when starting the next entry.

- Maintain double line spacing throughout the works cited page; do not add an extra space between entries.

- Organize entries alphabetically by author. If there is no author, use the title and maintain alphabetical order. If the title starts with a number, act as if the number has been spelled out, and alphabetize according to the first letter of the written version of the number. However, do not spell out the number in your entry if it is not spelled out in the actual title.

- Do not number your entries.

When it comes to formatting each entry, the MLA Handbook’s 9th edition has a simpler, more flexible set of guidelines than seen in previous editions. As we have access to information in so many ever-evolving formats, the handbook provides a list of core elements to include in each citation, noting that the list can be adapted (elements that aren’t available or don’t apply can be omitted) to suit the specifics of your source.

- Author.

- Title of source. (This is the title of the article or chapter or short story or webpage, etc.)

- Title of container, (This is the publication or website or book, etc. in which your source is contained.)

- Other contributors,

- Version,

- Number,

- Publisher,

- Publication date,

- Location. (This can include page numbers or URLs.)

Notice the punctuation that follows each item on this list. That is the punctuation you must follow in your entry and also represents simpler requirements than included in previous editions.

Additionally, for electronic sources, it’s recommended to include the date of access, and remove the “https://” from the URL as you’ll see in the sample. If the source includes a DOI (a direct object identifier) you can include that in place of the URL.

A Sample Works Cited Page

Showing is often better than telling when it comes to instruction, so here is the works cited page for this article. Any source referenced in the article is (or should be!) listed on this page, and every item on this page is referenced in the article.

Each entry is formatted according to MLA guidelines. And some of them were pre-made for me! Often, publications will format the content of a citation for you. Then, you just need to adjust the spacing.

Works Cited

“Common knowledge.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/common%20knowledge. Accessed Oct. 30, 2021.

Downing, Samantha. My Lovely Wife. Berkeley, 2019.

Grimm, Jacob and Wilhelm. “Hansel and Gretel.” Grimm’s Complete Fairy Tales, Margaret Hunt (Translator), Ken Mondschein (Introduction), Canterbury Classics, Nov. 1, 2011.

Hudson, John. “How Hitchcock's 'Psycho' Changed Cinema and Society.” The Atlantic, 16. June 2010, www.theatlantic.com/culture/archive/2010/06/how-hitchcock-s-psycho-changed-cinema-and-society/345186/. Accessed Oct. 30, 2021.

Lamotte, Sandee. “Diet drinks linked to heart issues, study finds. Here's what to do.” CNN Health, Oct. 26, 2020, www.cnn.com/2020/10/26/health/diet-drinks-bad-for-heart-wellness/index.html. Accessed Oct. 30, 2021.

“Plagiarism.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/plagiarism. Accessed Oct. 30, 2021.

Zimmer, Carl. “A New Company With a Wild Mission: Bring Back the Woolly Mammoth.” The New York Times, Sept. 30, 2021,www.nytimes.com/2021/09/13/science/colossal-woolly-mammoth-DNA.html. Accessed Oct. 30, 2021.

MLA Citations: Get Them Right Every Time

Make sure to check your citations carefully before you submit your work. They are an important part of your paper, and poor formatting could lose you marks. As a final note, make sure to check your individual institution's style guide for their rules on formatting your citations. While they may use MLA as a base, some schools add their own rules, too.

Want to improve your essay writing skills?

Use ProWritingAid!

Are your teachers always pulling you up on the same errors? Maybe you're losing clarity by writing overly long sentences or using the passive voice too much.

ProWritingAid helps you catch these issues in your essay before you submit it.